When we think of microbes, we often think of illness and disease. Widespread media fosters this connection by providing example after example of how bacteria and fungi can infiltrate and cripple our immune systems.

Using similar mechanisms, Microorganisms are also able to attach to and colonize steel surfaces, where they can “eat” materials using a variety of metabolic functions.

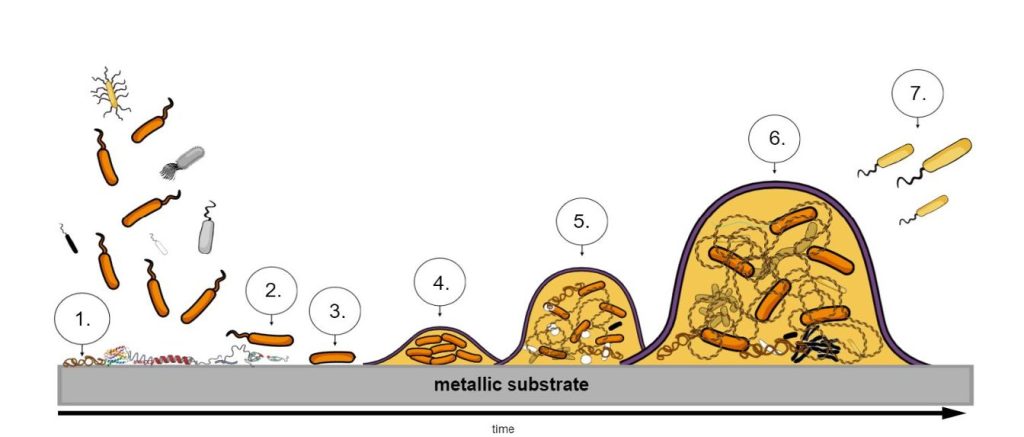

Figure 1: Biofilm formation on steel.

Many direct and indirect microbial corrosion processes can be involved, such as sulfate reduction, acid production, iron oxidation, and direct electron transfer, leading to challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of microbial contamination issues.

Microbial corrosion is estimated to cost our global economy around $625 Billion, and is documented extensively in industries such as oil and gas, water, marine transport, and Defense.

For almost a century, case studies implicating microbial corrosion have been documented across the globe. Most of these incidents occur in assets where water is naturally present, such as oil production systems, pipelines, floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) facilities, and marine structures like jetties and wharfs.

Why water? Because microorganisms need it to survive, colonise surfaces, and ultimately drive corrosion. Once they settle, these microbes form a sticky, structured community known as a biofilm. This biofilm is required to kick-start and maintain microbial corrosion.

Meanwhile, far from the oilfields and coastal infrastructure where MIC is typically expected, a very different story has been unfolding in the vast Australian outback. Mining operations, often assumed to be too dry, dusty, and harsh for microbial activity, are experiencing rapid and unexpected corrosion in critical assets.

The mining industry is critical to our way of life as a nation. Gold mining alone encompasses more than 350 operating sites nationwide and contributes around $20 billion AUD every year, a cornerstone of regional employment, national exports, and long‑term economic stability.

Figure 2. Corrosion Assessment in WA mining industry

When corrosion issues in such a vital industry are unknown or poorly managed, it affects everyone. Naturally, I was curious to determine the cause of these issues, and so I began inspecting assets across Western Australia for what I call ‘corrosion aggravators’.

Corrosion aggravators are factors that accelerate or intensify corrosion processes. These include time of wetness (the duration a surface remains moist), the presence of aggressive species such as chlorides, and galvanic interactions that occur when dissimilar metals are in direct electrical contact. Other contributors include oxygen availability, temperature fluctuations, pH changes, and mechanical damage that exposes fresh metal surfaces.

In parallel, I examined the fundamental requirements for microbial life, such as nutrients and suitable environmental conditions that allow microorganisms to grow and form biofilms.

Figure 3. Deposit build-up on steel assets results in increased risk of MIC.

Findings from these site inspections indicated that not only can microbial life exist, but it can thrive in the gold mining industry, even in gold cyanidation tanks.

As a corrosion engineer, this immediately raised a flag. Could microbial corrosion be occurring in the outback, despite the region being far from oceans, rivers, or other obvious water sources?

The more I investigated, the more the pieces fell into place. All the fundamental requirements for microbial activity were consistently available: a reliable water source, suitable temperature ranges, and a steady supply of nutrients. Even in these remote, harsh environments, the conditions were sufficient for microbes to grow, form biofilms, and potentially drive corrosion.

Figure 4. A corrosion nodule forming in a WA bore water tank is a sign of microbial corrosion.

Western Australian mine sites, especially gold processing plants, rely on process water; this water is pumped from deep underground bores and often contains a complex mix of dissolved minerals, picked up from the surrounding geology. In many regions of WA, this bore water is highly saline, rich in sodium chloride and other salts that can influence both processing performance and corrosion behaviour.

Process water is essential to almost every stage of gold extraction. It moves through every part of the plant, from leaching tanks up to 22 meters high to pipes, pumps, spray systems, and even access structures. In short, if it’s in the processing circuit, it’s touched by process water. And wherever water flows, so do the conditions that can enable corrosion, and, potentially, microbial activity.

Figure 5. Process water on a WA mine site with salts and other minerals is a corrosion aggravator.

Genetic testing of process water and potable water from three major WA mine sites confirmed what the site inspections had hinted at: microorganisms are not just present, they’re thriving, and in remarkable diversity.

They were detected in bore holes, fire‑water systems, pipework, safety showers, storage tanks, and even on equipment across the processing plant.

But the critical question remained: were these microbes actually causing corrosion?

Not all microorganisms can corrode steel assets, and not all assets on a mine site are exposed to microbially contaminated water. This gap made it clear that further investigation was needed. We began focusing on two key tasks: 1) identifying which assets were at genuine risk of microbial corrosion, based on their water exposure and operating conditions, and 2) conducting targeted visual inspections to look for tell-tale signs of MIC, localised pitting, under-deposit corrosion, black or slimy biofilms, or unusual corrosion morphologies.

These steps became central to understanding where microbial corrosion could be taking hold, and where it wasn’t.

Where bore water came into contact with carbon steel (‘site steel’), evidence of microbial corrosion began to appear. Because these assets were never designed with MIC risk in mind, and no operational measures existed for contamination control, microbial activity was able to grow and spread unchecked.

One case study centered on a bore water storage tank where coating degradation had left large areas of steel exposed. The tank displayed leaks and widespread general (uniform) corrosion, which, under normal circumstances, progresses slowly over many years. Uniform corrosion typically reduces steel thickness at a predictable rate and rarely causes rapid failures.

Microbial Corrosion behaves very differently. It is localised, attacking steel through concentrated pits or under-deposit zones. These focal points can lead to rapid metal loss, perforation, and unexpected asset failure, even when the overall structure still appears sound. In this tank, the corrosion pattern and field evidence indicated that microbial activity had accelerated the degradation well beyond what uniform corrosion alone would produce.

Figure 6. Perforations to site steel, and even stainless steel as seen above, can lead to safety concerns. This image was captured from a safety shower system on a Western Australian mine site.

Leaking and visibly perforated assets from multiple mine sites were documented and sampled using a newly developed DNA sampling kit, designed to preserve microbial DNA for at least 30 days at room temperature.

Figure 7. TECHT’s DNA sampling kits are designed for reliable field collection and preservation of microbial samples for up to 30 days at ambient temperature, enabling accurate molecular analysis of samples from remote locations.

Molecular analysis of these samples at the TECHT Laboratory revealed that diverse populations of potentially corrosive prokaryotes were concentrated specifically at the failure locations, strongly linking microbial activity to the observed damage.

To further demonstrate causation rather than coincidence, we established controlled exposure tests using site‑representative carbon steel immersed in process water. Microbial communities collected from three Western Australian mine sites were used to inoculate the test systems, which were then maintained for a two‑month exposure period. This setup allowed us to directly assess whether the microorganisms present in mine‑site water could initiate or accelerate corrosion under realistic conditions.

Figure 7. Corrosion testing in the TECHT laboratory to determine the link between microbes in process water and corrosion.

After the two‑month test period, we inspected the steel coupons and measured their corrosion rates using weight‑loss analysis (see ASTM G1-90 & NACE SP0775). This method is straightforward: you weigh the steel before the test, weigh it again afterwards, and the difference tells you how much metal has been lost. It’s a standard and trusted approach in corrosion science because it clearly shows how fast corrosion occurs over time.

The results were striking. Steel exposed to the microbial communities from mine sites showed nearly double the metal loss compared with the control samples that had no microbes added. In other words, the microorganisms were actively accelerating corrosion.

Although this work is still in the early stages, and there is much more to learn about the microbes thriving in mining environments, the findings highlight a genuine concern: MIC is likely an active and aggressive corrosion mechanism, even at inland mine sites once assumed to be low‑risk.

Looking ahead, the focus will be on developing early warning systems and targeted solutions. TECHT is currently mapping native microorganisms throughout the mining industry through the BioTECHT Division, which to date has not been achieved before. Other industries already use a range of strategies to manage MIC, design improvements, smarter materials selection, chemical dosing programs, and cathodic protection, to name a few. The challenge for mining is to determine how these tools, along with emerging technologies, can be adapted or scaled to their unique conditions. Knowing the makeup (genus, species) of the microbial communities we have to face is a critical first step.

The question now is clear: How do we leverage both new and proven technologies to extend asset life, reduce financial losses, and improve safety across the mining industry?

And this is exactly where our passion lies at TECHT. We’re committed to delivering innovative asset integrity solutions, backed by reliable testing and expert consultancy, to support a more sustainable future, helping industry move forward with confidence, resilience, and smarter engineering.

Management of Microbial Corrosion in the mining industry starts with asset owners and the teams that drive Australia’s mine sites. Knowledge of microbial corrosion can empower more informed decisions that save operating costs, reduce incidents, and ultimately lead to a safer, more productive site.

BioTECHT is a division of TECHT specialising in Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC).

We work closely with our clients to develop tailored and innovative microbial corrosion solutions.

Contact us to find out how we can help you.

References

Tuck, B., Watkin, E., Somers, A. Machuca L.L. A Critical Review of Marine Biofilms on Metallic Materials. npj Mater Degrad 6, 25. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-022-00234-4

NACE International. (n.d.). Economic impact. http://impact.nace.org/economic-impact.aspx

Tuck, B., Salgar-Chaparro, S. J., Watkin, E., Somers, A., Forsyth, M., & Machuca, L. L. (2022). Extracellular DNA: A Critical Aspect of Marine Biofilms. Microorganisms, 10(7), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10071285

Tuck, B., Investigating Multispecies Biofilms on Steel Surfaces in Seawater and

Biofilm Inhibition by a Novel, Multifunctional Inhibitor. Doctoral Thesis, Curtin University, 2022.

Tuck, B. Understanding Natural Biofilm Development in Marine Environments, A Review: Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (MIC), Technical, Water and Wastewater Technical Group, Webinar Recordings. Australasian Corrosion Association, 2021. https://www.corrosion.com.au/understanding-natural-biofilm-development-in-marine-environments-a-review/

Standards:

Corrosion by weight loss analysis: ASTM G1-90(1999)e1, Standard Practice for Preparing, Cleaning, and Evaluating Corrosion Test Specimens https://store.astm.org/g0001-90r99e01.html

Corrosion by weight loss analysis for oilfield applications: NACE SP0775-2023, Preparation, Installation, Analysis, and Interpretation of Corrosion Coupons in Hydrocarbon Operations

For a full list of articles by the Author: Benjamin Tuck (0000-0002-4201-9864) – My ORCID